On Nov 4-7th 2019 I had the opportunity to attend The Conservation Symposium, which aims to bring together those working on conservation issues within South Africa.

I enjoy this conference because it takes me out of my academia bubble and transports me into the ‘on the ground’ conservation practice realm. Students and academics make up a small portion of the attendees, outnumbered by NGOs, consulting companies, government organizations, attorneys, reporters, and filmmakers.

The main theme that struck me throughout this conference is the need to understand the human dimension to ensure effective conservation planning and management. Below I discuss a few of the key insights I had in relation to this topic.

This year they had the first ever session dedicated to indigenous knowledge (IK) in conservation. It was interesting to see how as a country we are actually quite ahead of the game in the inclusion of IK in conservation publications. But the thing that irked me during this session was that the audience laughed at almost all mentions of local taboos (an example of which is that some indigenous people believe that touching a certain tree species causes women to immediately start menstruating). I think this demonstrates how far we have yet to go in reframing our mindsets to see conservation not from a typical westernized view, but from a more inclusive, open-minded framing.

I also noted how all of the IK-related talks were in a terrestrial setting. I searched ‘South Africa indigenous knowledge marine’ in Web of Science and found zero papers investigating the use of IK in marine conservation. But, this made me remember an interesting poster at this year’s WIOMSA symposium where they interviewed local fishers along the South African coastline asking if water temperatures were changing, and reported areas where fishers’ knowledge differed from temperature changes monitored by scientists. We still have a long way to go with integrating IK into conservation management, and I think we will see a lot more marine conservation studies incorporating aspects of local communities in the near future.

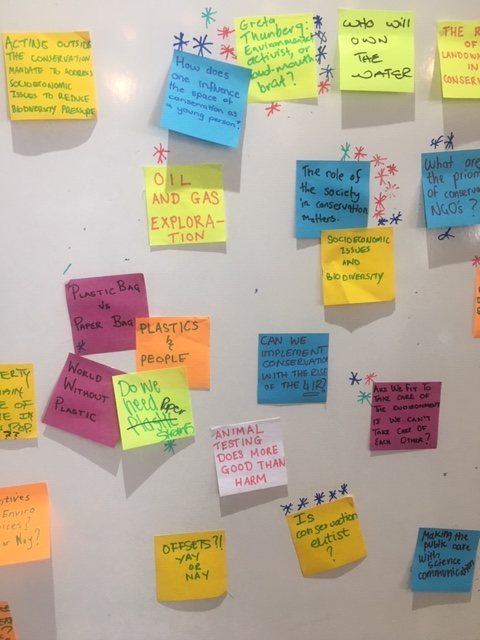

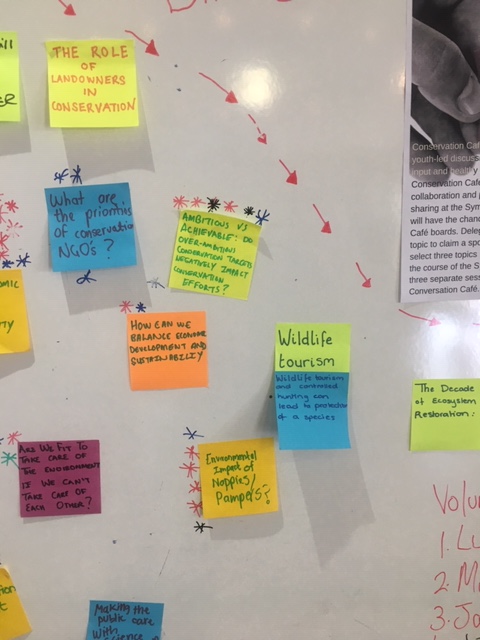

This year the symposium also introduced the Conservation Café, which involved youth-led discussions on conservation topics chosen by young (<35 yrs) attendants. During the tea breaks, we wrote on a white board what we wanted to discuss or added stars next to those topics on the board that we were interested in (seen in pictures below). In the session I went to, we talked again about IK within conservation, but also about capitalism and the goal of conservation. It was a lot of discussing problems, but one of the solutions I took away was that as youth we need to use our voices on social media, and also broaden our social circles in real life (or IRL as the kids say these days) to actively ‘market’ sustainable lifestyles and ‘make conservation cool again’.

Lastly, there were some very interesting talks on how people perceive our parks within the country. Nyiko Mutileni gave a talk on her work where she interviewed local communities just a few km outside of Man’ombe Nature Reserve, asking if they have every entered the reserve, and if they benefit from the reserve. Many local people had never even heard of the park, only ~3% had entered the park, and most believed they did not benefit from the park because they could no longer access natural resources. Another talk by Dr Izak Smit described how he interviewed visitors of Kruger National Park to understand how they perceived conservation. Most visitors do not believe that conservation areas should be focused on making money, or that we humans should actively manage nature through ‘harsh’ management such as culling. But most surprising to me was almost half of the interviewees believe that humans are separate from nature rather than interconnected through ecological processes. Dr Smit mentioned how this is partly driven by the fact that while 1.9 million people visit Kruger annually, only ~1% actually get out of their cars, walk in the bush, and physically connect with nature. Our disconnect with the natural world is a major issue of our time (shown by the fact that I had to mention ‘in real life’ in the previous point), and protected areas will be fundamental to our individual and societal resilience as we face ever increasing uncertainties on this Earth.